Moral absolutes and apostasy

(Originally published at What's Wrong With the World. Link to original post at 'permalink' below.)

Philosophers like to philosophize, and surprisingly enough, they are not all immune from the influence of "the current." If a new movie comes out exploring an old subject, you will find that somewhere, some philosopher has decided that this requires that he write something new about it. That wouldn't be a bad thing in itself, but it is a bad thing when philosophers come to the wrong conclusions about a type of thing that has been hashed out long ago, and it's especially odd if they do so in a way that implies that this time it's different because of the peculiarities of the case at issue in the new movie, book, etc.

I have been surprised to find something of this phenomenon occurring concerning the new Scorsese movie, based upon a book by Shusako Endo, Silence.

Disclaimer: I haven't watched the movie nor read the book. I'm writing this post not to argue about the correct interpretation of Scorsese or Endo but rather to argue about a certain wrong conclusion that is being drawn about our actual duties to the Lord Jesus Christ, prompted by the scenario (or, for some people, a modified version of the scenario) in the movie. So if you think that I'm wrong to take it that the book/movie endorses the legitimacy of public acts of apostasy, at least in some cases, don't worry about that. My concern is entirely with whether we should endorse it.

Here's the basic scenario, as I understand it: A serious Christian, the priest Rodrigues, is being psychologically coerced into performing a public act of renouncing his Christianity. In the particular case in the movie the public act takes the form of stepping on a picture of the face of Christ (or in some cases of the Virgin Mary). To coerce him, the wicked persecutors are horribly torturing to death other people in front of him. These people (I'm told) have already apostatized themselves, though I myself don't believe that that should make a difference to what is right for Rodrigues to do. Some with whom I've discussed this issue have suggested that we could "up the ante" by imagining that those being tortured to death are your own children, though this is not literally the case in the movie/book. In the movie/book, Rodrigues eventually seems to hear the voice of Jesus Himself telling him to go ahead and trample the picture. Whether Jesus is actually talking to him is, of course, up for interpretation, but that's what he believes, and on that basis he gives in.

Let me say as clearly as I possibly can that, in rejecting the legitimacy of apostasy even under such horrific circumstances, I am not denying any of the following:

--A really good person might very well crack under horrible psychological pressure and publicly deny Christ. Any of us might crack under that sort of coercion.

--We should have great compassion for someone who gives in under such circumstances.

--Coercion is a greatly mitigating factor, perhaps even to such an extent that, where there is enough coercion, we could conclude that the person's personal freedom had been completely overridden by the coercion and that he was therefore not to blame for his actions for that reason.

Notice, however, that what none of these say is that the action was morally justified. Indeed, even if one goes so far as to say that a person is entirely excused because his personal freedom was overridden by the psychological or physical torment, that implicitly presumes that the action would have been wrong if undertaken freely, much less calculatedly. It is crucial that we maintain a strict distinction between pitying Rodrigues and making up a philosophical theory that justifies his action. For if stepping on a picture of the face of Christ is justifiable by ethical theory, then it would not be necessary even to try to resist the persecutors until one breaks under the pressure. The persecutors could simply lay out their ultimatum and threats and, if one considers their threats credible, one could then choose to give in to their demands right at the beginning and spare everyone suffering.

One attempt to justify Rodrigues can, I think, be easily dealt with. This is the attempt to say that his action is a "mere motion of the foot" and that what would be really wrong would be his rejecting Jesus in his heart. As long as he isn't apostatizing in his heart, goes this argument, it is completely okay to make a mere "foot motion" to save others from suffering.

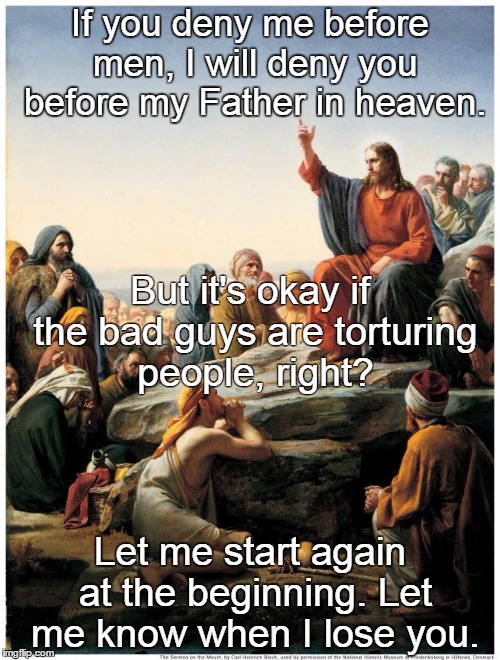

This attempted justification makes a mockery of what is clearly taught in Scripture--that it is wrong to deny Jesus before men. (Matthew 10:33, Luke 12:9) In order to deny Jesus before men, one must use language or some external sign that is understood by other people. But any such sign could be said to be "merely external," up to and including the words, in a commonly understood language, "I deny and renounce Jesus Christ." One could say that uttering such words is "merely a movement of the tongue" or "merely a breath of wind out of one's mouth" and that, as long as one doesn't really deny Jesus "in one's heart," it's okay to apply consequential considerations and go ahead and say the words. And the same for the three young men and the fiery furnace. Bowing down to the image is a "merely external" act. So is pouring a libation to the emperor. So go ahead. It isn't really denying Jesus in your heart!

This sort of reasoning would negate the importance of resisting such acts that both Scripture and common sense attach to them. Scripture, overtly and repeatedly. Common sense, because we all know that the very reason that the persecutors are demanding the external act is because it is meaningful. Everyone involved in the situation realizes that they wouldn't be doing all these horrible things to try to force Rodrigues to trample on the face of Jesus Christ if it were a "mere foot movement." It is a significant speech act.

The next argument is really just a plea from the extreme nature of the coercion involved. When Jesus said that we should never deny him before men, could he really have had in mind a scenario in which the evil men are torturing your children to try to get you to engage in some symbolic act of apostasy?

This argument is related to the claim, made in a 1989 philosophical article about Endo's book, that Rodrigues faces a genuine moral dilemma in which the command to love God with all your heart is at odds with the command to love your neighbor as yourself. (See quotes here.)

The problem with this whole approach is that it assumes that the act of publicly denying Christ is not intrinsically wrong. Those of us who believe in intrinsically wrong acts have been bombarded forever with increasingly horrific scenarios: But surely if the bad guys were going to do this, you would do that, right? There is this curious idea that the ethical concept of an intrinsically wrong act can be rendered null and void if only the consequences of refusing to perform it--even consequences brought about manipulatively by evil men--are bad enough! But the whole point of an intrinsically wrong act is that nothing can justify it, period. Hence it doesn't matter what the bad guys are going to do.

I don't know precisely what Jesus' phenomenology was like while here on earth. I would guess that he had, at least prior to his resurrection, something like our experience of having some thoughts or ideas implicit and some thoughts explicit. I'm certainly not going to say that when he solemnly warned his followers that they must never deny him before men he was explicitly thinking of a situation where the bad guys attempted to coerce them by torturing their children before their very eyes. But Jesus is obviously teaching about a coming time of persecution, and bad guys have been sadistically creative in their methods of coercion since time immemorial. There is no reason whatever to think that Jesus was not saying that denying him before men is an intrinsically wrong act, that he realizes that persecutors will try all sorts of horrible things to get us to comply, but that we should cling to him and do all that we can to remain firm, no matter what. St. Paul quotes what was probably an early Christian hymn or creed to this effect:

If we suffer, we shall also reign with him. If we deny him, he will deny us. (2 Timothy 2:12)

Indeed, Jesus actually says that we should "hate" our parents and children in comparison to our love for him. (Luke 14:26) Even allowing for Eastern hyperbole, the whole point of such an utterance seems to be that, if there is an apparent conflict between our duty to remain true to Jesus and our duties to those people, our duty to Jesus takes precedence. (Look, Ma, no ethical dilemmas!)

The attempt to use the commandment to love your neighbor as yourself to create a dilemma for Rodrigues is highly artificial. Since when does the second great commandment mean, "There are no intrinsically wrong acts"? Or, "Utilitarianism is true"? Or, "You are obligated to do anything, including acts you might otherwise have considered intrinsically wrong, to prevent the suffering of your fellow man"?

The injunction to love one's neighbor as oneself is a broad moral principle that in no way endorses consequentialism in ethics. Nor, for that matter, does it command any one particular act. In contrast, Jesus' injunction not to deny him does clearly command against a particular act.

That denying Jesus before men is an intrinsically wrong act is clear not only from Jesus' teaching and other biblical teaching (e.g., the three young men in the fiery furnace) but also from the very nature of religion and Christianity. The whole point of religious commitment is that it is ultimate commitment. There are things to which one has given one's whole self, things to which one is absolutely committed. Christianity, as taught not just in verses about not denying Jesus but throughout the whole fabric of the New Testament (and Judaism in the Old) is similarly about absolute commitment of oneself. We are to take up our cross and follow Jesus. To live is Christ and to die is gain. We are crucified with Christ, yet Christ lives in us. We are to count all things as loss for the excellency of the knowledge of the Lord Jesus. We present our bodies a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable, which is only our reasonable service.

To the Christian, God, as revealed in the Son, Jesus Christ, is the ultimate value. If we don't have Him, we have nothing. We are therefore willing to die for him, to suffer for him. Nothing else is more important. Literally nothing. Nothing can compete with Him, nothing can take His place. If evil men choose to do evil things, yes, even evil things to those we love, that does not change the nature and importance of our own commitment to the Lord Jesus Christ. It is to be absolute, because that is part of what it means to be a Christian. There is no point at which one says, "Okay, now that's too much. This is where I get off the train. That consequence of my following Jesus Christ is just so bad that I can't possibly be expected to continue not denying him. This is the place where it all changes." If you think that ratcheting up the bad things the bad guys can do can make a difference, you fundamentally misunderstand the nature of what Christ calls us to.

A Christian's commitment to Jesus isn't a commitment with a utilitarian asterisk.

(In passing, I endorse the point made by this commentator: If one is going to use the commandment to love one's neighbor as oneself in this context, then it would be at least as justifiable to trample on the image of Christ to save oneself from torture and death as to do so to save others. One isn't supposed to love oneself less than one's neighbor.)

Bill Vallicella (who is not endorsing the ethical dilemma claim) makes one other argument that it is legitimate for Rodrigues to trample the picture:

[G]iven the silence of God, it is much better known (or far more reasonably believed) that the prisoners should be spared from unspeakable torture by a mere foot movement than that God exists and that Rodrigues' exterior act of apostasy would be an offence [against] God...

I have already discussed the "mere foot movement" claim. Now I want to discuss the epistemic argument. It is a little odd that Vallicella here alludes to the silence of God. Perhaps he is alluding to the fact that, until Jesus seems to speak to Rodrigues in the book (and endorse trampling), God is silent in the sense that he sends no sensible sign directly to Rodrigues himself. God doesn't write across the heavens, "Thou shalt not trample." God doesn't smite the persecutors dead.

But so what? Christianity is a revealed religion. Insofar as one is a Christian at all, one believes that God has not been silent. "God, who at sundry times and in diverse manners spake in time past unto the prophets hath in these last days spoken unto us by his Son." (Hebrews 1:1)

Do we have Cartesian certainty that God exists and that Christianity is true? I would say no, but I would also say that Cartesian certainty (the same certainty I have that 1 + 1 = 2) is not necessary for absolute personal commitment. That's a big topic, but it's one that Vallicella cannot decide in one sentence. Certainly Christianity itself seems to presume that the evidence given is sufficient for absolute commitment, so the burden would seem to be on a philosopher who wishes to argue that only a relative, defeasible kind of commitment, commitment up to the point where the bad guys are going to do something really bad to someone if you don't publicly deny Jesus Christ, is possible on the basis of the evidence we have for the Christian revelation.

But that isn't the same thing as starting a sentence with, "Given the silence of God..." Obviously, if Christianity were just made up out of our heads, if God had never revealed Himself in Jesus Christ, if Jesus had never told his followers that he was one with the Father and that they must never deny him, we'd be in a much different situation! Then it might be legitimate to start a sentence on this topic with, "Given the silence of God..." Why would you let other people be tortured to death for a religion you don't have good reason to believe is true? Duh, as the kids say.

But if you do have very good reason to believe that Christianity is true, then you have very good reason to believe that God has not been silent, that you should be absolutely committed to Jesus Christ, and that therefore you shouldn't publicly deny Jesus Christ no matter what. It's just false to pit our ethical intuition that we should spare others from suffering against a putative "silence of God" when a major point of Christianity is that God is there and is not silent!

Utilitarianism will be the death of us. Perhaps the physical death, but much more plausibly the spiritual death. There is nothing especially philosophically virtuous about applying a calculus of "doing the least harm" to every scenario that comes up. From a Christian perspective, such a calculus is often just plain wrong. If we are to discuss such scenarios with any seriousness, we need to take seriously the possibility that Christianity is true and can be known to be true. If that is the case, it smashes utilitarianism to smithereens, and we are called to the most radical commitment of all.

No comments:

Post a Comment