Easter 2018: If He Rose At All, It Was As His Body

(Originally published at What's Wrong With the World. Link to original post at 'permalink' below.)

Dale Allison is a New Testament scholar regarded by some as an orthodox Christian, despite some rather odd aspects of his scholarship. For example, William Lane Craig says of Allison’s book Resurrecting Jesus, “I have never seen a more persuasive case for scepticism about the historicity of Jesus’s resurrection than Allison’s presentation of the arguments.” (From an exchange between Allison and several Christian philosophers in Philosophia Christi, vol. 10, no. 2, 2008, p. 293.) Craig takes it that Allison does conclude that the resurrection occurred despite Allison’s skepticism, and Craig takes this to be a testimony to the strength of the case (p. 294), but others are free to disagree with this characterization. For one thing, Allison has very strong doubts about the concept of bodily resurrection and hence refuses to commit himself to a belief that Jesus was raised bodily from the dead (exchange, pp. 316-319). The most he will say is that, in some appearances or other, which he does not think we are justified in claiming were much like those recounted in the Gospels, “[T]he disciples saw Jesus and...he saw them.” (Exchange, p. 334).

And even granting that much objective factuality to the resurrection, according to Allison, depends heavily on one’s prior worldview, which he thinks can be justified only by the work of theologians and philosophers, if such a thing is possible at all. (Resurrecting Jesus, p. 351)

What Allison is probably best known for is his widespread use of the concept of grief hallucinations and accounts of alleged paranormal appearances of the dead. He thinks that such accounts bear suggestive similarities to whatever is left of the Gospel resurrection narratives when higher criticism is done with them--a shredding process with which he seems quite willing to cooperate.

In short, Allison appears to believe in, at most, some version of what is known as the “objective vision theory” of Jesus’ resurrection rather than the bodily resurrection and to be somewhat hesitant about whether even that much can be justified in a rational fashion. I myself would not be inclined to refer to someone with that position as one who has been convinced that Jesus rose from the dead on the basis of historical argument.

Readers may wonder why I begin an Easter post with such a long survey of the views of a particular New Testament scholar. The summary is to serve as an introduction to quite a strange quotation from a different book by Allison, Constructing Jesus. The quotation represents precisely the wrong conclusion about history and Christianity.

In the pages preceding this quote, Allison has been talking about the quest for the historical Jesus. He characterizes his own historical research as having chiefly negative effects. It awakened him from his “dogmatic slumbers”--that is, it taught him to believe that much that is in the Bible about Jesus and that he believed previously is probably not true. At the same time this process still allows him to think that there is a factual basis for some very attenuated statements, such as that “Jesus had an exalted self-conception.” Allison wraps up thus:

While it may be an “emotional necessity to exalt the problem to which one wants to devote a lifetime,” and while I am proudly an historian, I must confess that history is not what matters most. If my deathbed finds me alert and not overly racked with pain, I will then be preoccupied with how I have witnessed and embodied faith, hope and charity. I will not be fretting over the historicity of this or that part of the Bible. (Constructing Jesus, p. 462)

Lofty sentiments, these, which could be echoed by a noble unbeliever.

Christianity is first and foremost an historical religion. According to Christianity, certain events in history are indeed what matter most. “If Christ is not raised,” says St. Paul, “We are of all men most miserable.” (I Corinthians 15:14)

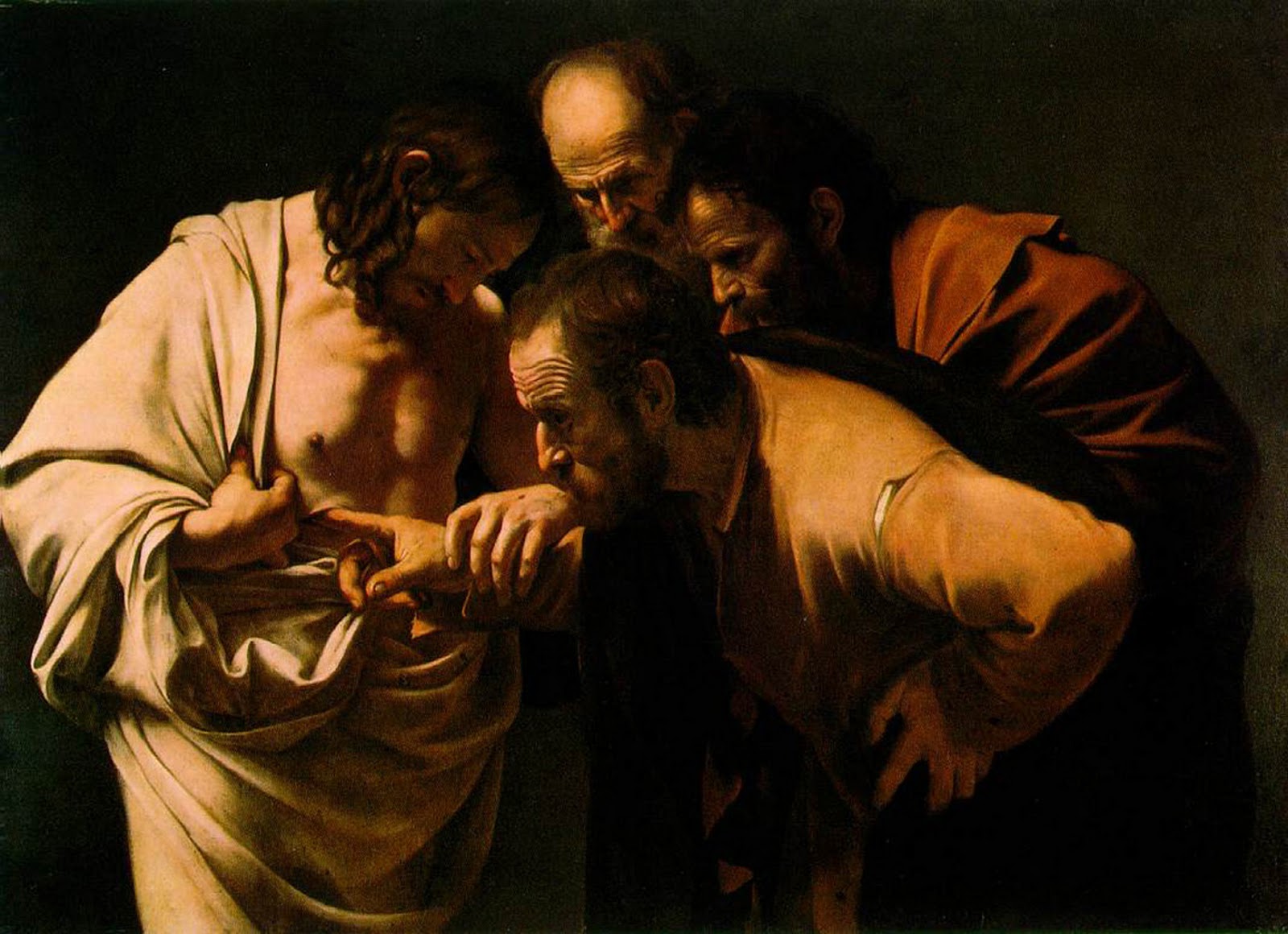

Contrast the far more orthodox view represented by John Updike’s “Seven Stanzas at Easter.”

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells' dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

It was not as the flowers,

each soft Spring recurrent;

it was not as His Spirit in the mouths and fuddled

eyes of the eleven apostles;

it was as His flesh: ours.

The same hinged thumbs and toes,

the same valved heart

that--pierced--died, withered, paused, and then

regathered out of enduring Might

new strength to enclose.

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

analogy, sidestepping, transcendence;

making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the

faded credulity of earlier ages:

let us walk through the door.

The stone is rolled back, not papier-mache,

not a stone in a story,

but the vast rock of materiality that in the slow

grinding of time will eclipse for each of us

the wide light of day.

And if we will have an angel at the tomb,

make it a real angel,

weighty with Max Planck's quanta, vivid with hair,

opaque in the dawn light, robed in real linen

spun on a definite loom.

Let us not seek to make it less monstrous,

for our own convenience, our own sense of beauty,

lest, awakened in one unthinkable hour, we are

embarrassed by the miracle,

and crushed by remonstrance.

Does the historicity of “this or that part of the Bible” matter? Indeed it does. But if one is convinced of the robust, physical historicity of the events central to Christianity, and if one is convinced by strong evidence, so that one’s reason is integrated with one’s emotion, then one’s deathbed can find one not fretting but rather rejoicing.

O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?

Thanks be to God who giveth us the victory through Jesus Christ our Lord.

A joyous Easter to our readers!

No comments:

Post a Comment