The beard and the heap

(Originally published at What's Wrong With the World. Link to original post at 'permalink' below.)

What is a sorites paradox, and how does it apply to biblical criticism? The paradox of the sorites or heap arises from the fact that if we add a single grain of sand to others, there is not a sharp line at which we say that we have a heap of sand. If we take one grain away at a time, there is not a sharp line at which it ceases to be a heap. Yet (mark this) there are cases that fall unambiguously on the side of "heap" or "no heap."

What is a sorites paradox, and how does it apply to biblical criticism? The paradox of the sorites or heap arises from the fact that if we add a single grain of sand to others, there is not a sharp line at which we say that we have a heap of sand. If we take one grain away at a time, there is not a sharp line at which it ceases to be a heap. Yet (mark this) there are cases that fall unambiguously on the side of "heap" or "no heap."

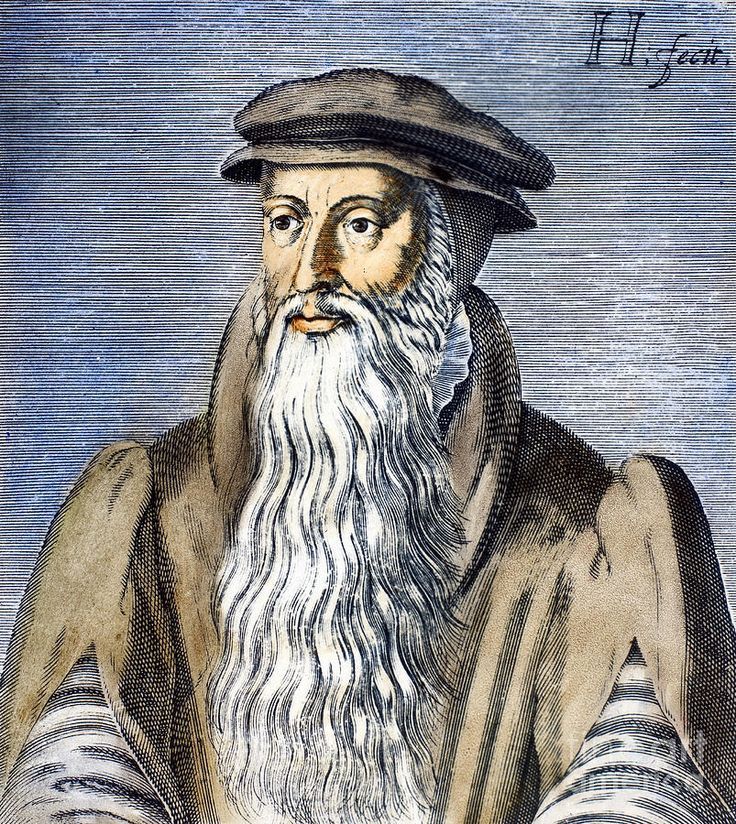

We can also think of this as a beard problem. When does a man have a beard, and when does he just have a five-o-clock shadow? There are fuzzy cases (pun intended) where we are unsure what to say. Yet this does not mean that there are no unambiguous beards and no unambiguously clean-shaven men.

Those making a misleading use of the term "paraphrase" in biblical studies will trade on the fact that there is no sharp line between garden-variety paraphrase, loose paraphrase, and completely different content. Hence they will ask something harmless like, "Do you believe that the Gospel authors sometimes paraphrased Jesus' words?" and thus try to pressure one into a false dilemma: Either one accepts wild "transformations" such as changing, "My God, why have you forsaken me?" into "I thirst," or inventing (on the basis of theological reflection) entire scenes in which Jesus utters "I am" sayings, or else one is an unlearned wooden literalist fundamentalist who thinks we must have a verbatim transcript of Jesus' words.

This is simply a failure to recognize that the absence of a sharp line along a quasi-continuum between A and not-A, between beard and no beard, between ordinary paraphrase and utter invention, does not mean that there are no clear cases.

Sorites issues come up in biblical studies in other areas as well. For example, consider my statement here that the world of biblical studies cannot be divided neatly between "liberals" and "conservatives." My point there was that one needs to consider positions and arguments on a case-by-case basis rather than labeling someone as a "conservative" and then trusting everything he says or disagreeing with everything said by a "liberal." But the fact that scholarship lies on a quasi-continuum and that evaluations have to be nuanced and are sometimes mixed does not mean that there are no biblical scholars who can reasonably and informatively be labeled "liberal" or "conservative." Again, the existence of a continuum does not mean that there are no clear cases.

Then there is my statement here that "when a conceptual parallel is close enough it becomes a type of verbal parallel, and a distinction between verbal and conceptual parallels can become artificial if pressed too hard." But it doesn't follow that there are no clear-cut cases in Scripture where one incident is definitely the same as the other or different from one another or where Jesus is using the same words as he does in a different scenario.

Moreover, there are places where we can talk about purely verbal matters or matters that are purely stylistic. My next post about the Gospel of John will concern some of these. For example, if in some speech by Jesus in John the Greek word "kai" is used to express a contrastive meaning (like "but"), where Luke (if he had reported the same scene in Greek) would have been more likely to use the Greek word "de" (which more expressly states a contrastive meaning), this really is a purely verbal matter. Jesus may well have been speaking in Aramaic in a given scene reported in John anyway, and "kai" may be a better parallel for the Aramaic all-purpose conjunction waw, but that doesn't mean that a Synoptic author would be making anything other than a legitimate verbal translation decision if he chose to render Jesus' "waw" using Greek "de." So the fact that there is not an extremely bright line between matters of conceptual content and mere matters of verbal style (or translation or paraphrase) does not mean that there are no questions or issues that fall unambiguously on one side or other of that divide.

The question, "Did Jesus expressly claim to have existed before Abraham, did he unambiguously identify himself with the 'I am,' Yahweh of the Old Testament, in the course of making this claim, and did this occur in a scene separate from anything in the Synoptics and recognizably the same as the scene recounted in John 8?" is an unambiguous matter of important conceptual content that should not be brushed off with vague talk of "paraphrase." The question, "How did Jesus express a contrastive conjunction, was he speaking Greek or Aramaic, and is John's Greek or Luke's Greek closer to the way that Jesus habitually expressed contrast by a conjunction?" is really a purely verbal matter that doesn't need to trouble anybody. It falls clearly on the other side of the line.

Don't be bullied by the beard. If Jesus didn't historically say, in a recognizable fashion, in a separate scene from anything in the synoptics, that he and the Father are one, then John is telling a shaggy dog story. And that ain't a paraphrase.

No comments:

Post a Comment